In the first post of this series, I discussed some of the reasons why writers might choose to publish with a small press rather than self publishing or querying agents. In this post, I’ll take a look at some of the “cons”: reasons why you might NOT want to publish with a small press. Some of these may be addressed in more detail in a third post.

Why Not Publish with a Small Press?

You’ll Probably Make Less Money.

First, be aware that small presses often don’t pay advances; they often pay only royalties. That means you probably won’t see any money from your book until after it releases.

Second, even if you leave aside the issue of advances, there’s data that suggests that authors who publish with Big Five Presses typically make more money than authors who publish with small presses. Hannah Holt found this to be true of children’s books, although her data is a bit old (2017).

This point may NOT be true of genres like romance or fantasy that sell directly to the reader. Many romance readers devour indie romance, especially in digital form, and there are successful indie writers who do make a living. The internet and digital publishing have enabled small presses and self-published authors to compete in the online market, even if not in brick and mortar stores.

Third, if you publish with a small press, you don’t get all the royalties, as you would if you self publish. The press takes a cut. Some writers have found that the benefits of working with a small press don’t outweigh the loss of royalties. Writer Beware reminds writers to ask “Does the press add value?” What are they doing that you can’t easily do yourself, and is it worth giving up a chunk of your royalties for that? The answer will vary from writer to writer and from one press to another.

Your Books May Not Be Sold in Bookstores

If I may be allowed to make a sweeping generalization, I’d guess that most authors write because they love books and want to be involved in producing them. Speaking only for myself, I have many happy childhood memories of visiting the library or the bookstore and finding new authors.

Unfortunately, brick and mortar stores simply can’t stock all the books published in a given year. There are thousands of books published every day, and there just isn’t room for all of them in even the largest bookstore. Often, small press authors get their books into stores only by arranging with local stores to sell on the books by commission. (And if, like me, you have some social anxiety, the prospect of approaching a bookstore owner and asking them to stock your book may be intimidating. Especially if they want you to talk on the phone or in person rather than by email!)

Note, though, that small presses vary a good deal in terms of distribution. Some very reputable small presses DO get their books into brick and mortar stores. But if you’re looking at a new small press or a micro press, don’t expect Barnes and Noble stores all over the country to carry your book.

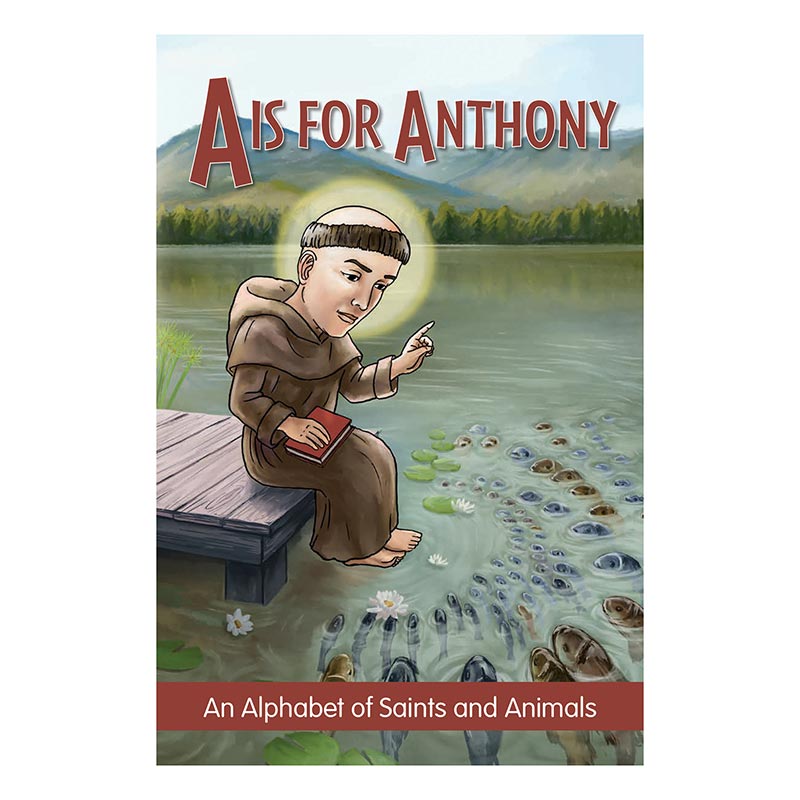

My experience: You won’t find my debut romance in a Barnes and Noble. Interestingly, though, if you walk into a Catholic bookstore, you may find my little booklet about saints and animals (published under a different name).

This in-store presence isn’t my doing. It’s because the book was published by a small press (Aquinas Press) connected to a major Christian company. They serve a niche market and they know how to distribute their products to their market. If you’re writing for a very specific market, a small press with good connections may be able to get your product into the appropriate stores for that market.

Your Print Books May Cost More

As I mentioned in the first post of this series, many small presses use print-on-demand (POD) technology to produce paperbacks or hardcovers. While this option is flexible, it costs more per book than offset printing. As a result, paperback books produced by a small press using POD may cost more than a book of equivalent length published by a Big 5 Press.

One of the complaints I sometimes hear from writers working with a small press is “Why do the books cost so much?” or even “Our books cost too much!” What those writers mean is that readers aren’t always willing to pay the high price for a paperback from a writer they’ve never heard of, ESPECIALLY if the book isn’t as attractive or professional-looking as the books they see in Barnes and Noble.

The answer to “Why do the books cost so much?” is “Because they are printed through POD.” In many cases, the solution is to lean more heavily into ebooks, which is where many small presses make their profits. But if you have visions of selling print copies in person at fairs, conventions, or other events, be aware that it can be hard to price the books such that you still make a profit.

You May be Expected to do Most or All of the Marketing

This point is a tricky one. Folks working with small presses will sometimes tell you “all writers have to do marketing.” To a certain extent, that’s true. Even Big 5 publishers have a limited marketing budget, and that budget isn’t distributed evenly/equally. Some books get more of a marketing push than others, and whether your book is one of the favored few will be beyond your control. Unfortunately, BIPOC writers and other marginalized writers report getting less marketing support from their publishers than popular white authors.

However, there’s a big difference between a small press that asks you to do SOME of the marketing and one that asks you to do ALL of the marketing. I’ll talk a bit more about this in the next post. For now, I’ll just say that some small presses will pay for social media ads for your book, post the book on NetGalley, BookSirens, or BookSprout so it gets advance reviews, submit it to review sites, and promote it widely through their own social media and readers groups. There are other small presses that don’t do those things. As a writer, you want to publish with a press that will put some money into marketing your book.

Be aware, too, that review sites like Kirkus or Publisher’s Weekly are more likely to review books produced by major publishers. While it’s possible to buy a review with one of these sites, a small press may not have that kind of budget, and those reviews may not be taken as seriously by libraries and book stores.

My experience: For me, marketing has become one of the biggest factors in evaluating a small press. Like many writers, I find marketing/promotion to be my weak point. Going forward, I only want to work with small presses that are going to assist with marketing.

Not All Small Presses are Created Equal

My next post in this series will focus on this point, but it’s so important that I’m going to mention it here, too. Setting up a small press is easy. Managing a successful small press that continues to thrive in a changing world is NOT easy. If you decide to work with a small press, be aware that you’ll have to do a LOT of due diligence figuring out which presses are worth subbing to. If you want examples of what can go wrong, check out the Writer Beware blog, which reports on problems writers have with specific presses. The main Writer Beware website also has an excellent article about questions to consider when you sub to small presses.

Leave a comment