If you’ve ever spent time in Book Twitter or Book Threads, you’ve probably seen the perennial fights about whether romance requires a HEA, or “happily-ever-after” ending. It’s a discussion that crops up several times a year. The participants in the debate may change, but the same discussion points come up over and over again.

Most romance readers and writers will tell you that yes, romance does require a HEA, or at least a happy-for-now (HFN), because that’s one of the genre conventions. In my experience, though, there’s a lot of confusion about what that does and doesn’t mean. In this post, I’ll try to clear up some of the confusion.

What’s a HEA?

While there are many different kinds of happy endings, in the context of romance novels, a HEA means that the romantic leads at the center of the plot end up in a romantic relationship, and the relationship is a positive thing, something the characters are happy about. If characters are forced into an unwanted marriage and left unhappy about it at the end of the story, that isn’t a HEA.

A HEA doesn’t always involve matrimony, by the way. While many romance novels end with marriage and children, those aren’t requirements. Romance can end with the leads being unmarried romantic partners, as long as the characters are happy with the situation. Some romances end with the lead characters in a polycule rather than a couple. Still counts as romance!

“Happy for now” endings also qualify: we don’t necessarily need an epilogue to prove that the characters are still together 20 years later. What matters is that at the end of the story, the leads are romantically together.

What’s a romance?

Part of the confusion in these debates stems from the fact that the word “romance” has multiple definitions.

People unfamiliar with modern romance fiction are often quick to point out that stories like Romeo and Juliet or Titanic are very romantic, despite the tragic ending. And they’re right. There are many classic love stories that do not end happily. No one in romancelandia is denying that.

When folks in romancelandia say “romance requires a HEA,” we don’t mean “all love stories have to end happily.” Romance arcs in other genres can have tragic, bittersweet, or ambiguous endings. We only mean that there’s a specific genre of fiction called “romance” and one of the requirements of that genre is a happy ending to the romance arc.

To put it another way, if you’re publishing a book today and you label it a romance novel, romance readers are going to expect the leads to be romantically together at the end of the novel.

Oh yeah? Says who?

When I jump into the HEA debate and try to explain all this, I’m somtimes told “That’s just your opinion. Your opinion isn’t necessarily right.”

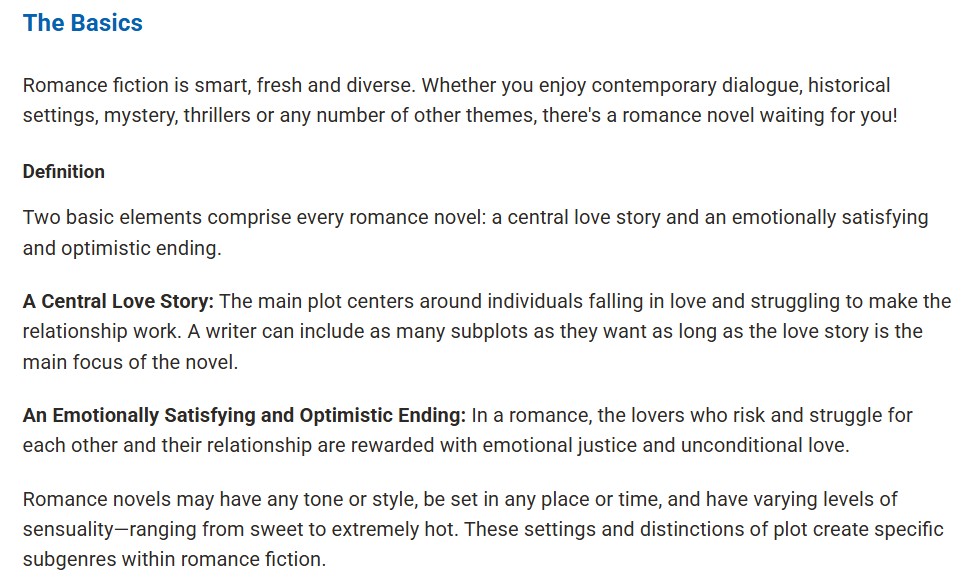

But this isn’t merely my personal opinion. It’s the view of professional organizations like Romance Writers of America (RWA). In their introduction to romance fiction, RWA defines romance this way:

RWA is only one (flawed) organization, and only a small percentage of romance authors belong to it. But my sense is that most members of the online romance community support the HEA requirement.

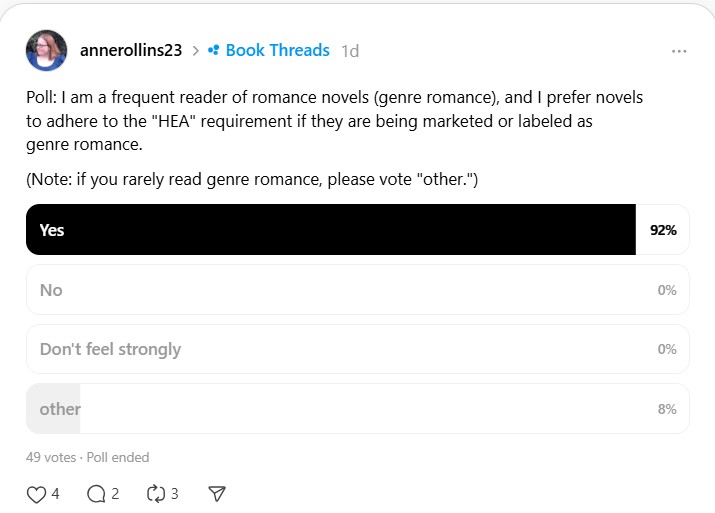

I’ve done informal social media polls on the subject a couple of times. Though I don’t have sample groups large enough to make the results significant, those polls tend to confirm that romance readers want their romance novels to come with the guarantee of a HEA or HFN.

Anecdotally, challenges to the HEA requirement usually seem to come from people outside the romance community. Sometimes challenges come from readers who like a wide range of endings for love stories. Other times the challenges come from writers who want to market their work as romance even if the love plot has a tragic or bittersweet ending.

This is part of what frustrates me about the HEA debates: it feels like outsiders march into our space and tell us that we’re doing it wrong. If you’ve ever wondered why romancelandia is so touchy/defensive when it comes to the HEA requirement, this is one of the reasons.

Open for debate

Before I sign off, I want to acknowledge that there are some gray areas— places where people might legitimately disagree about whether an ending is really a HEA.

For example, we’d generally say that if one or both of the lead characters in a novel die at the end, that’s not a HEA, and that story is a romantic tragedy rather than a romance. But what if you’re reading a paranormal romance in which a live human falls in love with a ghost? If the death of the living character allows them to be united with their ghostly love interest in the afterlife, is that a HEA? Does that story still fall into the romance genre? I suspect opinions would be split.

There are interesting and important conversations the romance community could have regarding what qualifies as a HEA in today’s romance novels. Unfortunately, those conversations get crowded out by the many posts claiming Romeo and Juliet is a great example of a romance with a tragic ending, despite the fact that it’s a play rather than a novel. I’d love to see us move beyond that!

Leave a comment